The Chatham Arts Council is investing in artists through our Meet This Artist series, introducing you to 12 Chatham County artists each year in a big way.

The fine folks at Hobbs Architects in downtown Pittsboro are powering our Meet This Artist series this year. Architecture is art, and the Hobbs crew values art in our community.

Take a look. Meet your very inspiring neighbors. Meet This Artist.

Mark McCombs didn’t grow up knowing he was going to be an artist, or even a teacher for that matter. His path into the art world began when he took over teaching a class on the intersection of math and art at UNC. After a student taught him the basics of origami, Mark discovered his passion for modular origami, which is based on the math principle of fractals, or repeating patterns, such as the ones seen in snowflakes. But the true muse behind Mark’s fractal art is his late brother Doug, a lifelong musician who died unexpectedly in 2015.

I invite you to read about Mark’s unique journey into the art world and how he is keeping his brother’s memory alive through his art.

How did you become a math professor? Have you always been interested in math?

When I was growing up, my family moved around a lot. By the time I graduated from high school, we’d moved 13 times. I came to Chapel Hill in 1978 to attend UNC. When I got to Chapel Hill, I decided I was done moving — I really liked this place. I started off as an English major because I was convinced I was going to be a writer. Midway through my junior year, my dad says to me, “So, what are you going to do with your English degree?” And I thought, “Oh gosh, I guess with an English degree I’ll end up teaching high school.” But in my heart, at the time, I felt there was no way I could be a teacher. It’s not that I thought teaching was somehow beneath me. I had no confidence that I would be good at it. So I switched my major to math and minored in English. I entered the PhD program in math at UNC with no real reason for being there other than to just stay in school. I discovered very quickly that it’s the wrong place to tread water. It was a very humbling experience. I also realized that I’m not a research mathematician – I actually am a teacher.

When I was growing up, my family moved around a lot. By the time I graduated from high school, we’d moved 13 times. I came to Chapel Hill in 1978 to attend UNC. When I got to Chapel Hill, I decided I was done moving — I really liked this place. I started off as an English major because I was convinced I was going to be a writer. Midway through my junior year, my dad says to me, “So, what are you going to do with your English degree?” And I thought, “Oh gosh, I guess with an English degree I’ll end up teaching high school.” But in my heart, at the time, I felt there was no way I could be a teacher. It’s not that I thought teaching was somehow beneath me. I had no confidence that I would be good at it. So I switched my major to math and minored in English. I entered the PhD program in math at UNC with no real reason for being there other than to just stay in school. I discovered very quickly that it’s the wrong place to tread water. It was a very humbling experience. I also realized that I’m not a research mathematician – I actually am a teacher.

I stayed in the PhD program for as long as I could. I finished the coursework and started working on a dissertation, but realized I was faking it and finally told my dissertation advisor, “Look, I’m going to embarrass you because I don’t know what I’m doing, so I’m just going to quit.” Thankfully she said, “Well, let’s get you a master’s degree.” So I switched from a pure math topic to a teaching topic, wrote a master’s thesis on teaching math, and finished that year.

During my last year in graduate school, I got a fellowship that was created to attract STEM people to teaching high school. In exchange for the stipend, you promise to complete an accelerated 12-month Masters of Teaching program and teach for a minimum of three years in a public high school in North Carolina. I ended up teaching at Jordan High School in Durham. I taught ninth grade geometry, five periods in a row. I was terrible at it because I couldn’t do the discipline. Jordan’s a good school, but I was 29 and I looked like I was about 17. Most of my classes ended up being like the Andy Griffith Show episodes where Andy went to Mt. Pilot and left Barney in charge back in Mayberry. I knew by October that I was in the wrong job. I resigned at the end of the year.

During my last year in graduate school, I got a fellowship that was created to attract STEM people to teaching high school. In exchange for the stipend, you promise to complete an accelerated 12-month Masters of Teaching program and teach for a minimum of three years in a public high school in North Carolina. I ended up teaching at Jordan High School in Durham. I taught ninth grade geometry, five periods in a row. I was terrible at it because I couldn’t do the discipline. Jordan’s a good school, but I was 29 and I looked like I was about 17. Most of my classes ended up being like the Andy Griffith Show episodes where Andy went to Mt. Pilot and left Barney in charge back in Mayberry. I knew by October that I was in the wrong job. I resigned at the end of the year.

So the clouds parted and the angels sang or whatever that summer of 1989 when the job I am in now, in my 31st year, was advertised by the UNC math department. They created a position for someone to teach undergraduate math classes and coordinate the TA training in the math department. I applied for that job and was hired.

I’ve enjoyed the blessing of having found why I’m here, at least professionally. I’m really good at it and I really like it. My dad spent his whole professional life as a computer programmer and systems analyst. I remember him telling me and my brothers, “You know, even on my busiest and most frustrating day, I know I’m doing what I want to do.” We all thought, well, we’ll never have that. But Doug found it in music, my older brother Kirk found it in law, and I found it in teaching.

How did you start teaching the class on math and art?

I’m not required to do research but I’ve done some curriculum development. For example, I created this first-year seminar on math and art that I teach. That’s been another one of those grace moments for me because I love art. I always have, but I was always scared of it. It’s like when I tell people I’m a math teacher, they say, “Oh, I hate math,” or “I can’t do math,” or “I’m not good at math.” My response has always been, “You know, if I was at a party and someone said, ‘Okay, we’re going to do some art now…’ I would say,’Uh, I think my toilet’s running. I gotta go.'” But when I was asked to take over this math art seminar 12 years ago, I said yes because I thought it was time to stop being afraid.

I’m not required to do research but I’ve done some curriculum development. For example, I created this first-year seminar on math and art that I teach. That’s been another one of those grace moments for me because I love art. I always have, but I was always scared of it. It’s like when I tell people I’m a math teacher, they say, “Oh, I hate math,” or “I can’t do math,” or “I’m not good at math.” My response has always been, “You know, if I was at a party and someone said, ‘Okay, we’re going to do some art now…’ I would say,’Uh, I think my toilet’s running. I gotta go.'” But when I was asked to take over this math art seminar 12 years ago, I said yes because I thought it was time to stop being afraid.

I thought it would be challenging but stimulating to do it. But the first few years I taught it, I felt in some ways like I was a fake. I was scared. I didn’t want to let my students down. As time went on, I started to feel less intimidated. Then about eight or nine years ago, on the first day of class, one of the students asked me if we were going to do origami. I told him that I didn’t know how to do it, so he offered to teach us. He taught us how to make some one-sheet classical origami and showed us a couple of modular origami designs. Something happened to me that day. I realized this art form was accessible to me, and spoke to me.

When I teach the class now, I tell my students that if you’re sitting here right now worried that you don’t have any art in you, believe me, I feel your fear, but be patient with yourself. Be kind to yourself and you’ll find that it’s in there.

How do you teach students about how math and art intersect?

The goal is to try to help students explore the perspective that math isn’t numbers — it’s patterns. It’s how you can do math even if you’re afraid you can’t. And I guess that’s what I’ve come to learn about myself in terms of art. Even though I was afraid I couldn’t do it, it’s in me. Thinking mathematically isn’t the ability to calculate five digit square roots in your head. Thinking mathematically is being able to make sense out of your experience by recognizing patterns.

The goal is to try to help students explore the perspective that math isn’t numbers — it’s patterns. It’s how you can do math even if you’re afraid you can’t. And I guess that’s what I’ve come to learn about myself in terms of art. Even though I was afraid I couldn’t do it, it’s in me. Thinking mathematically isn’t the ability to calculate five digit square roots in your head. Thinking mathematically is being able to make sense out of your experience by recognizing patterns.

There’s a really amazing documentary called “Achieving the Unachievable” on MC Escher, which focuses on the actual mathematics behind one of his pieces. But it’s more than just the math. He wasn’t a professional mathematician. He loved math, and it informed his art, but it wasn’t why he made art. So we look at that through this notion of symmetry and the mathematical idea of making a tiling using regular geometric shapes. There are only three shapes you can use: a square, an equilateral triangle, or a hexagon, because the angles have to meet and the interior angles have to add up to 360. Those are the only regular geometric shapes that do that.

Escher’s genius is in being able to take a hexagonal tile and modify an edge so that it rotates onto itself or reflects onto itself so those pieces fit together. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle, but now you see lizards crawling in and out of each other and into infinity, or whatever. That’s mathematical art, I guess. He’s responding to the way our brains process patterns.

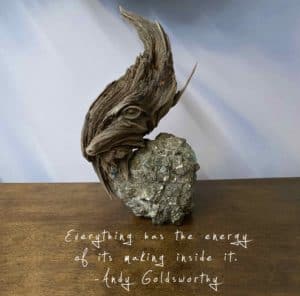

The other artist that I always share with the class–and this is one of my biggest joys with teaching this class–is showing the Andy Goldsworthy documentary called Rivers and Tides. In the documentary, he calls his process “having a conversation with nature.” He talks about how he’s not the creator, but rather the conduit. Much of his work is sculpture using nature, and part of the work is that eventually nature will reclaim it. The documentary follows him around to the different commissions where he’s making pieces. There’s always this idea that there are numbers and geometry in what he’s doing. I believe what he’s really doing is experiencing grace through harmony.

How did you get started with becoming an origami artist?

In November of 2015, my younger brother, who was just an incredible musician, died unexpectedly of a heart attack at 52. He was my hero. After his memorial service, I brought home all of his recordings so I could digitize and archive them for his son Miles, who is also a guitarist. As I’m sitting on my couch with headphones on, I’m folding paper, and all of a sudden this kind of stuff starts happening with the paper for the first time. I don’t know what my spiritual orientation, is but I have no doubt that my brother Doug was a part of it. I feel like it’s just one more gift he has given me.

In November of 2015, my younger brother, who was just an incredible musician, died unexpectedly of a heart attack at 52. He was my hero. After his memorial service, I brought home all of his recordings so I could digitize and archive them for his son Miles, who is also a guitarist. As I’m sitting on my couch with headphones on, I’m folding paper, and all of a sudden this kind of stuff starts happening with the paper for the first time. I don’t know what my spiritual orientation, is but I have no doubt that my brother Doug was a part of it. I feel like it’s just one more gift he has given me.

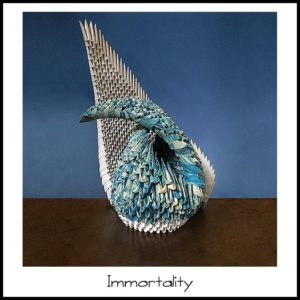

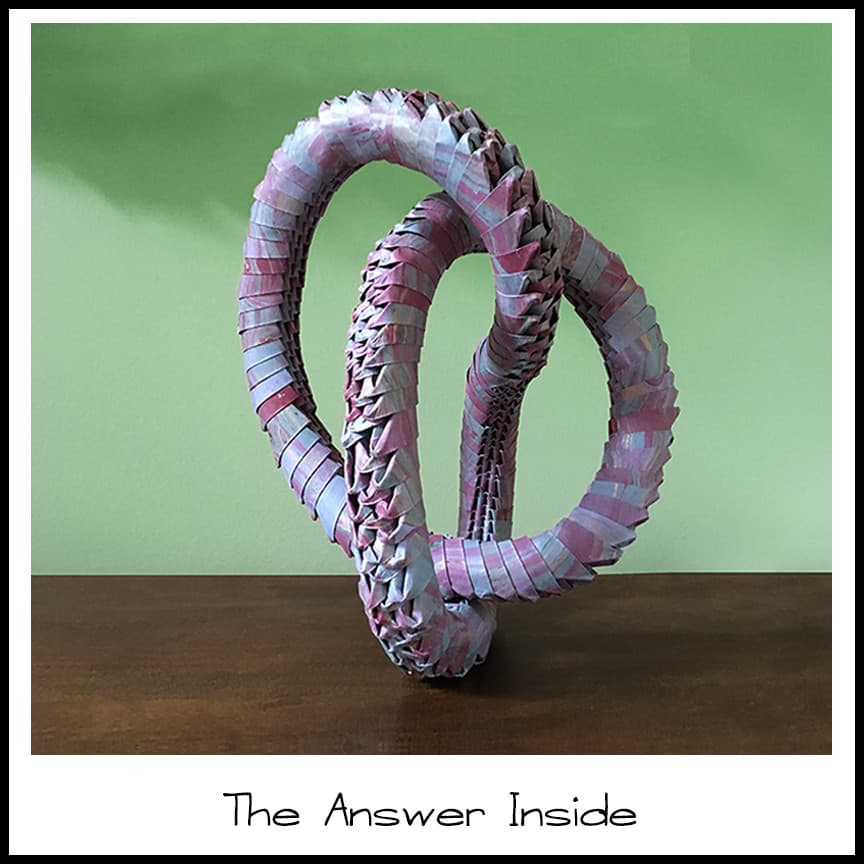

Modular origami was a miraculous discovery for me. You start with just a rectangle (three by five is the optimal proportion) and fold until you get a triangle. After you make a lot of them, you can link the triangles together consecutively. One of the fun things for me is how I can have a conversation with the paper as I fold and work with it. Ultimately it feels like the paper is in charge of things.

What is the process like in creating one of your pieces? Do you come up with an idea or sketch or does it just evolve as you go?

It just evolves. There are certain shapes that I know will just automatically start to happen when I put things together. I usually have an idea, but what really I hope will happen is that I find myself discovering the sculpture rather than creating it. Those moments remind me of the Michaelangelo quote: “I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.” If it’s not happening, I take the pieces apart and try something else. Eventually there will come a point where I’ll say to myself, “Okay, this isn’t working right now,” and I’ll just pick it all apart and then try something else. It’s not unlike the writing process where you write something, walk away, come back, and edit it.

It just evolves. There are certain shapes that I know will just automatically start to happen when I put things together. I usually have an idea, but what really I hope will happen is that I find myself discovering the sculpture rather than creating it. Those moments remind me of the Michaelangelo quote: “I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.” If it’s not happening, I take the pieces apart and try something else. Eventually there will come a point where I’ll say to myself, “Okay, this isn’t working right now,” and I’ll just pick it all apart and then try something else. It’s not unlike the writing process where you write something, walk away, come back, and edit it.

Tell me about the experience of having your work shown at the Bridges conference in Sweden and at Liquidambar gallery in Pittsboro.

The Bridges organization sponsors annual international conventions on the intersection of science, art, and math. Every year the conference meets in an amazing place. In 2007, I went to the one they held at the Banff Institute for Research and Study. At the time, I went with this perspective that I hope no one really notices I’m here because I don’t belong here. I don’t know how to make anything.

The Bridges organization sponsors annual international conventions on the intersection of science, art, and math. Every year the conference meets in an amazing place. In 2007, I went to the one they held at the Banff Institute for Research and Study. At the time, I went with this perspective that I hope no one really notices I’m here because I don’t belong here. I don’t know how to make anything.

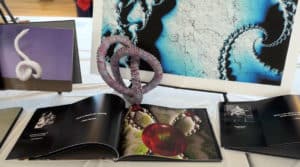

But once I started doing modular origami, I decided to submit some of my art to be included in the exhibition at the Bridges conference in Stockholm. Amazingly, they accepted two of the pieces — a sculpture and a fractal. This time when I went to the conference, I didn’t feel as much like a stowaway as I did before. It was still pretty overwhelming to walk into the gallery.

During the week of the conference, they had a blind auction with some of the artwork, with the proceeds going to cancer research. One of my sculptures was bought in that auction by one of the curators of the museum. The day before I flew back to North Carolina, I went to the museum to say goodbye to two people who sponsored and hosted us. Sitting on the counter when you walk in the door to buy your ticket at the museum is my sculpture.

During the week of the conference, they had a blind auction with some of the artwork, with the proceeds going to cancer research. One of my sculptures was bought in that auction by one of the curators of the museum. The day before I flew back to North Carolina, I went to the museum to say goodbye to two people who sponsored and hosted us. Sitting on the counter when you walk in the door to buy your ticket at the museum is my sculpture.

That experience gave me the confidence to go to Kitty at the Liquidambar Gallery in Pittsboro and say, “Hey, I make sculpture. I have some of my art in the car — can I show it to you?” She agreed, so I brought in a few pieces to show her. I remember her telling me that she’d never seen anything like that before. She then asked me if I’d like to be one of the featured artists in July at her gallery. On the first weekend that my work went up, I was there, along with some friends and family. It was pretty overwhelming. Seven of my pieces sold on the first day. I had paper with me so I could show people how to fold, which was really fun. I remember there was one little boy in front of me who was just mesmerized. At one point, he said to me, “Learning is awesome.” It kind of made me cry.

Have you been involved in any other exhibitions?

Have you been involved in any other exhibitions?

In October of 2015, the North Carolina Museum of Art opened their MC Escher exhibition. At the time, it was the largest exhibition of Escher’s original work ever presented in the U.S. During that summer, I got an email from the show director asking if I would sit for an interview to talk about math and Escher. They were going to have iPads set up at different locations in the exhibit where you could watch little videos, and they asked me to speak about the symmetry of tessellation. Before I sat for the interview, I called Doug and told him about the interview request. I told him that I wasn’t sure I was going to say yes because I felt like I didn’t belong in that conversation. I still remember him saying, “Well, you can say no, but you’ll need to leave the porch light on because I’m going to be there later tonight to kick your rear.”

So on Halloween night in 2015, my wife and I went to the pre-opening gala for donors to the gallery and people who contributed to the exhibition. A few days later, Doug died. So it’s poignant for me. It’s just hard.

What do you think Doug would say to you now about you being an artist?

What do you think Doug would say to you now about you being an artist?

He would say, “See? I told you.”

Doug used to say that tone is what allows us to experience moments of grace through harmony. It’s not just the harmony of the sound; it’s harmony with the world and with others. It was the idea that it’s not a gift unless you share it. So I’ve created a website to display my fractals and origami, infinitetonestudios.com. That’s really the best way for me to try to understand my art; it’s a gift I can share.

To see more of Mark’s work, visit his website.

What a lovely write-up about an incredible artist!

Insightful!